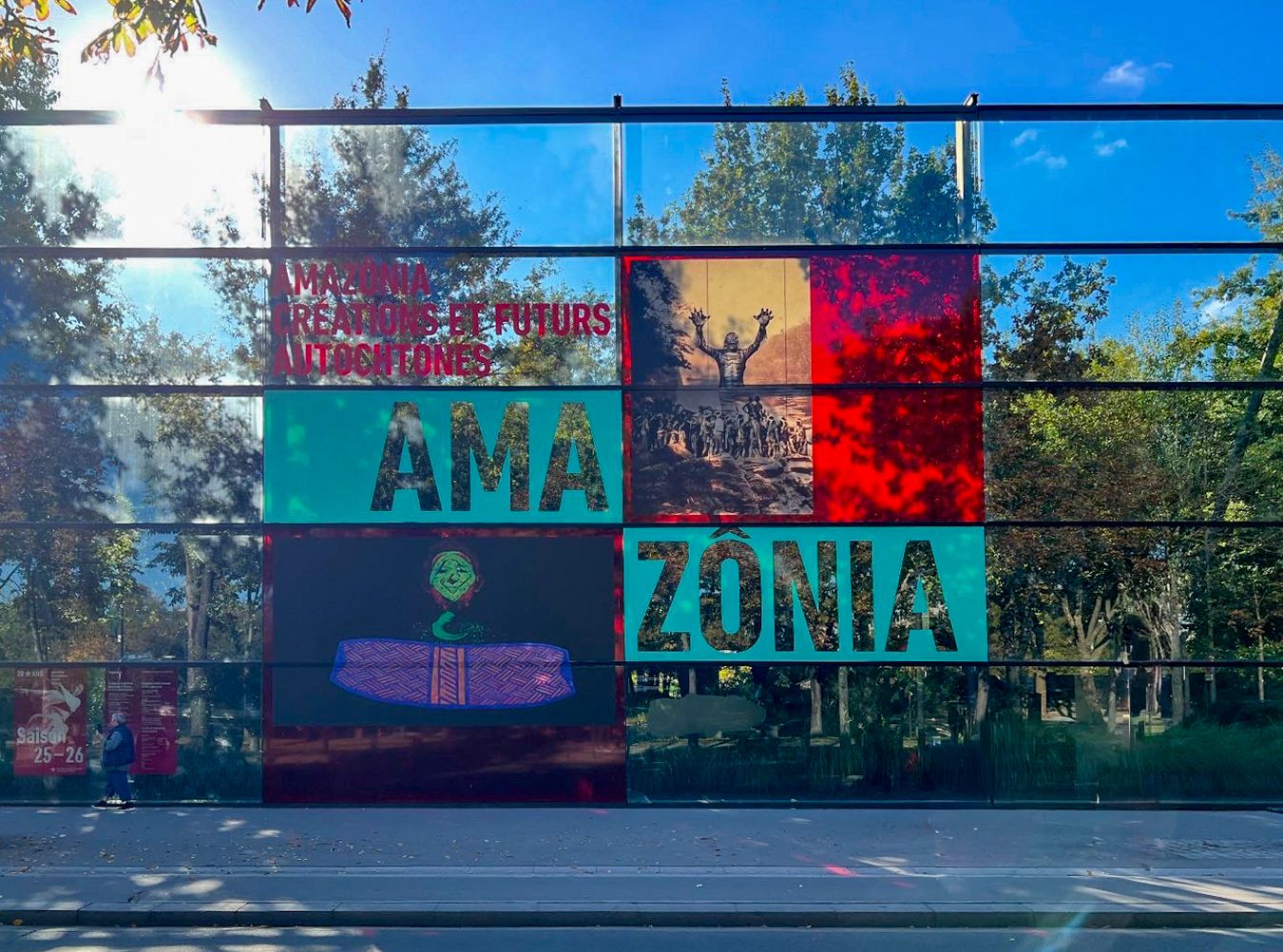

Musée du Quai Branly - Jacques Chirac façade with the exhibition's visual identity. Photo by the author, September 2025.

This is my first post of the year, and I'm starting with one of the exhibitions I loved most in 2025. It's made by two people from whom I always learn so much—artist and curator Denilson Baniwa, and curator Leandro Varison, deputy head of research at the Musée du Quai Branly - Jacques Chirac. Of course, this won't be an impersonal review—though really, what review ever is? I contributed to this exhibition as a scientific advisor and some of the collaborative works I was part of were selected for it, but I kept enough distance to be genuinely surprised by how effectively Leandro and Denilson realized their vision.

The exhibition's point of departure is a familiar problem: when we think about Amazonia, we usually picture a remote, inhospitable forest inhabited by Indigenous peoples whose traditional ways of life seem frozen in time—pure, unchanging testimonies to humanity's origins. Through this idealized lens, contemporary Amazonians often appear as degraded versions of what they "should" be.

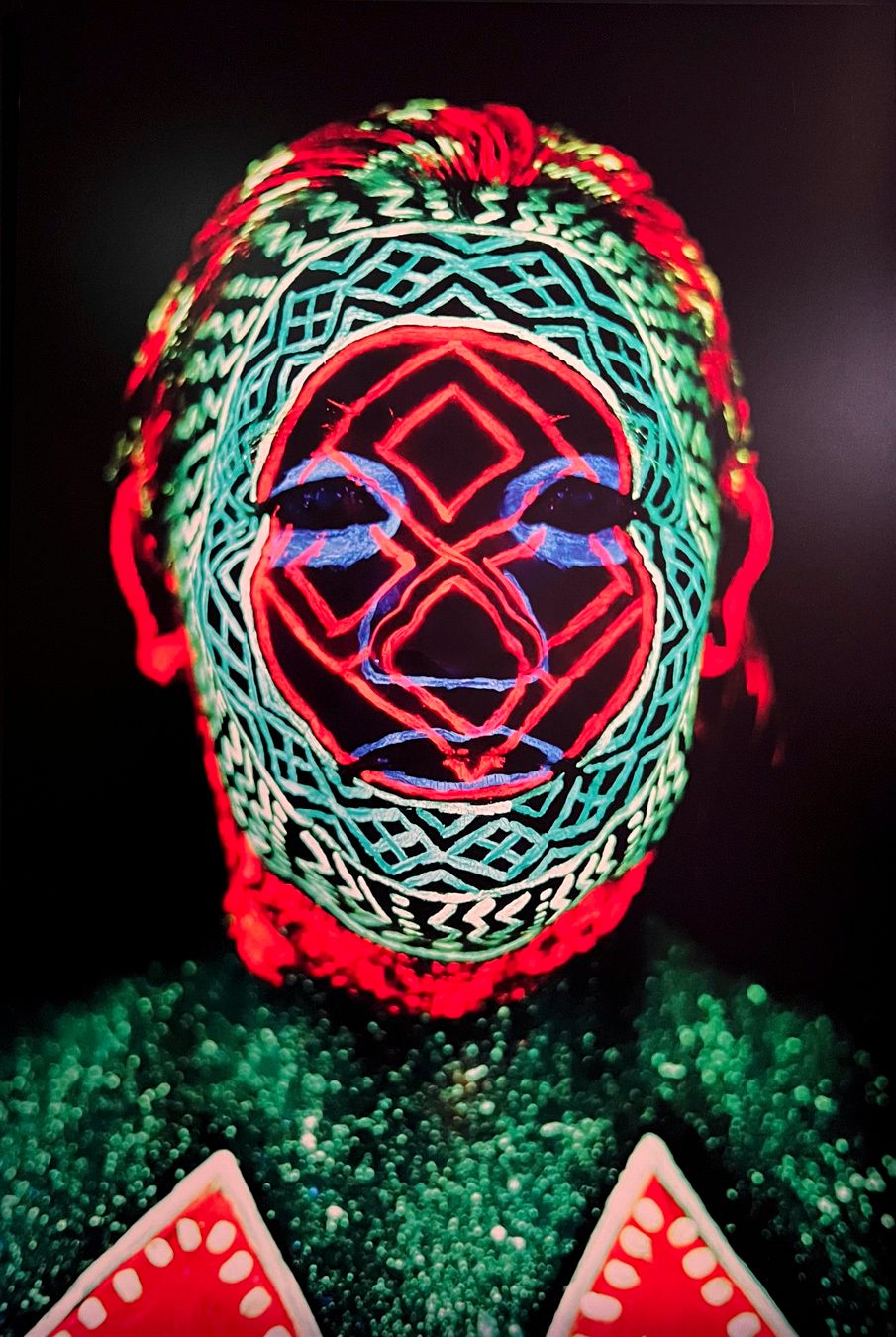

Paulo Desana's photograph from the series Pamürimasa, The Spirits of Transformation. Photo by the author, September 2025.

Amazônia: Créations et Futurs Autochtones, which closes in Paris on January 18th and reopens at the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, Germany, in March, deliberately challenges this exotic imagery. Where we expect the past, it shows us contemporaneity. Where we foresee unchangeable tradition or pristine nature, it reveals change, transformation, and cultivated forests. Where we anticipate inevitable destruction, it explores Indigenous futures that might help us reshape our own societies.

The most remarkable thing you learn from this show is that archaeology, ethnology, and contemporary art can flow together in a single conversation.

Typically, museums keep these three elements rigidly separated. You get archaeological artifacts in one room, ethnographic objects in another, and contemporary art somewhere else entirely. Or worse, you get them arranged as a timeline: ancient past → ethnographic present → contemporary future, as if Indigenous cultures moved in a straight line from "primitive" origins toward some inevitable endpoint.

Entrance room of the exhibition. Photo by the author, September 2025.

Denilson and Leandro refused this template. Instead, they wove archaeology, material culture, and contemporary art into an ongoing dialogue—treating them as equally valid ways Indigenous peoples have expressed their imagination about the same territories across time. A pre-Columbian ceramic vessel sits near a contemporary painting or an adornment collected in the 1960s, not because one came "before" the other, but because all three articulate related cosmological ideas through different media.

Connecting these different media challenges common sense about Amazonia by affirming that these aren't cultures "stuck in the past" or "losing their traditions"—they're people who have always experimented with available materials and media to express evolving ideas about their living worlds.

Final section of the exhibition. Photo by the author, September 2025.

The exhibition also offers a compelling lesson in the use of exhibition space.

Using the Musée du Quai Branly's 1,000-square-meter basement temporary exhibition room, the designers choreographed the public's journey through a play of compression and expansion. We start in a round room exploring the origins of people and forest, in which all the artworks dialogue across some distance. Then we pass through a small door that compresses the experience, leading us into intimate corridors created by the arrangement of glass cases showing how people decorate and produce the human body in Amazonia. From this body-to-body scale encounter, where we connect with the intricate details of the exhibition pieces, the space gradually opens again around stories of human-environment relationships, eventually delivering you to a large open area where images of Amazonian futures close the show. In a complement, audio guides you through the space, creating an immersive environment that extends beyond what you see. The rhythm across media—dense artifact displays, large photographs and paintings, sound and video installations—creates an elegant balance that kept me engaged through multiple visits.

Visitors viewing Jaider Esbell's work Letter to the Old World (2018-2019). Photo by the author, September 2025.

The exhibition's publicity was also a great success. It started with the choice of Paulo Desana's work for the posters and catalogue cover. Desana's images, which play precisely with the traditional and the contemporary in Amazonian body painting, populated Paris streets and subway stations. As we know, because it offers one of the greatest concentrations of cultural activities in the world, Paris is one of the hardest places on earth to get attention for anything, let alone for an exhibition challenging deeply held assumptions about Amazonia and Indigenous peoples. The choice of Desana's image proved right—people flocked to the show.

Exhibition publicity being installed in the Paris subway. Photo by the author, September 2025.

But perhaps the exhibition's most important gesture was leaving space for unresolved questions.

The opening week included a colloquium—"Existe-t-il un Art Amazonien?" (Is there an Amazonian art?)—that brought together Indigenous artists, curators, and scholars to grapple with fundamental issues the exhibition itself couldn't fully resolve. As curator Hans Ulrich Obrist argues, curating exhibitions has much to do with the art of posing questions. Connecting the premiere to this public conversation sustained critical momentum and questioned the exhibition's own premises.

The colloquium revealed just how contested even the most basic terms really are:

"Amazonia" itself is a settler-colonial term. Responding to the question in his dialogue with anthropologist Andréa-Luz Gutierrez-Choquevilca, Uitoto artist Rember Yahuarcani pointed out that in Peru, "Amazonian art" has long meant exotic forest imagery made by mestizo settlers, not Indigenous creators. He deliberately calls his work "Indigenous contemporary art" as an act of political resistance and self-representation.

Rember Yahuarcani, Medianoche en el río Ampiyacú, 2016. Photo by the author, September 2025.

But "Indigenous" brings its own problems. Carlos Jacanamijoy, in conversation with curator Paz Núñez Regueiro, discussed the racialization embedded in ethnic categories. Arguing for "desfolklorization," he observed that the art world tends to "use these ethnic terms only when artists are Black or Indigenous." No one says "white artist Kandinsky," for example.

Jacanamijoy also gave a stunning painting performance with the Third Coast Percussion ensemble, painting a large canvas on the ground while they played his interpretation of the Uakti-Philip Glass album Águas da Amazônia. In this performance, he connected his vision of art as "portals" between cultures to Philip Glass's own cross-cultural musical explorations—demonstrating rather than merely describing how art can transcend categorical boundaries.

Carlos Jakanamijoy, Despertar antes del alba, 2023. Photo by the author, September 2025.

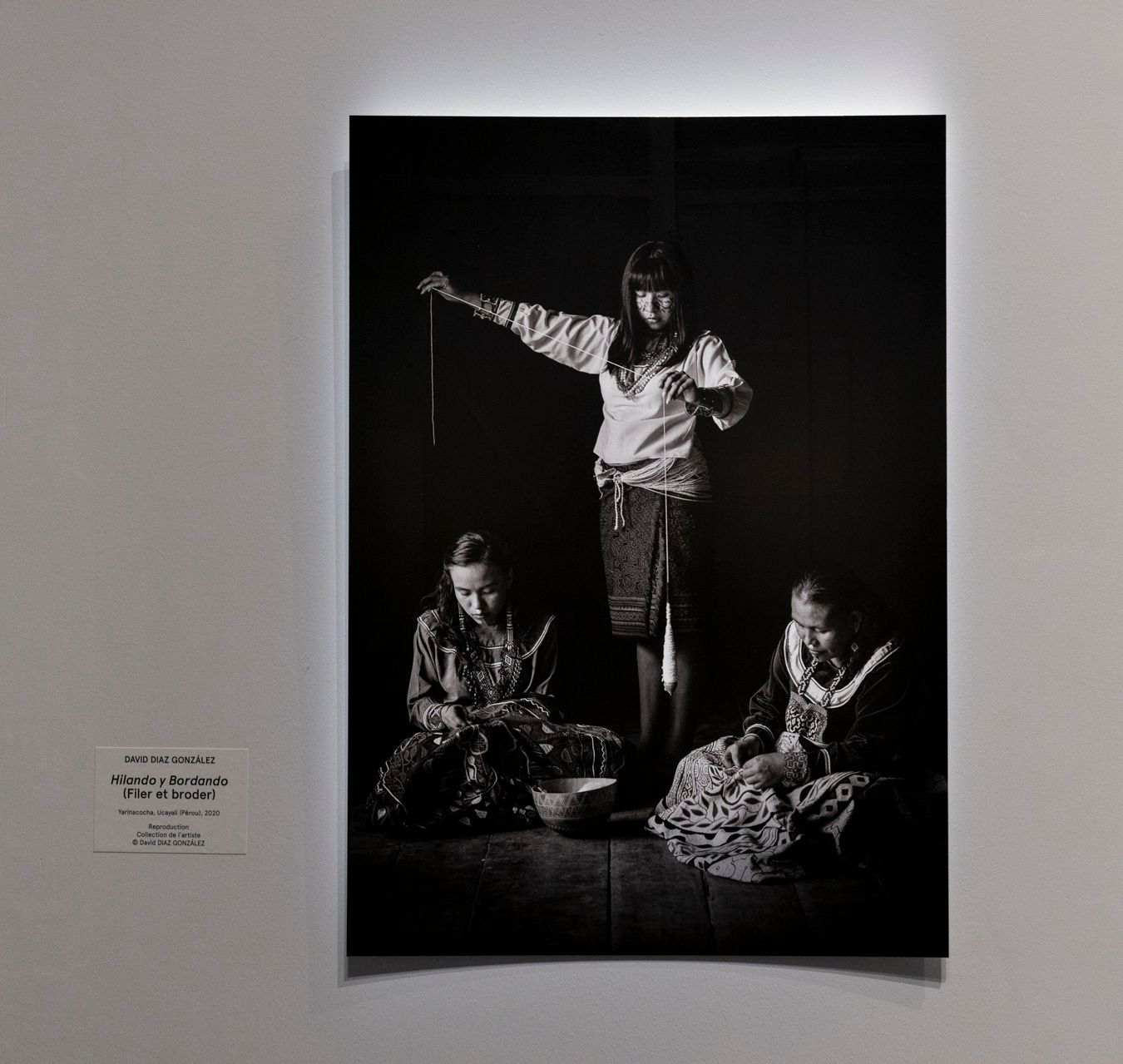

Yet the question of categorization cuts multiple ways. David Díaz Gonzales, speaking with Leandro Varison, described how engaging with photography deepened his awareness of his Indigeneity and cultural pride—but without the "folklorization" denounced by Jakanamijoy. His portraits of Shipibo-Conibo families in urban Pucallpa challenge stereotypes of Indigenous peoples as necessarily rural or isolated. Photography, often criticized for objectifying others, became in his hands both "an act of rebellion" and a tool for cultural preservation.

David Díaz Gonzales, Hilando y Bordando, 2020. Photo by the author, September 2025.

In my own dialogue with Denilson Baniwa during the colloquium, he emphasized what might be called the cosmological foundations of artistic practice. For him, incorporating Indigenous perspectives into art history means recognizing that Indigenous people have always been treated as objects, not subjects, in that history. He drew on Baniwa cosmology to illustrate: art is the gift of Kowai, a more-than-human being known for his capacity for "building and destroying worlds."

From this affirmation, I understood that rather than individual expression—disinterested in the Kantian sense of the word—art becomes a negotiation with something far broader. Where Western art history centers on personal genius, the Baniwa see something more perilous. Making art becomes "like trying to survive the force of this entity." Artistic practice is a form of engagement with creative forces far greater than any individual artist.

As many commentators noted at the end of the colloquium, the overwhelming impression was the need for more spaces like this—more platforms to explore and develop these complex questions together.

Denilson Baniwa and Leandro Varison during one of the many public encounters that took place during the exhibition's opening week. Photo by the author, September 2025.

As a result, we can say that Amazônia: Créations et Futurs Autochtones represents a significant step toward a renewed view of Amazonia and its peoples. The exhibition builds on the groundbreaking path opened by Naine Terena's "Vexoa: We Know" (Pinacoteca de São Paulo, 2020-2021), which similarly rejected chronological organization and challenged the artifact/handicraft stereotype. Denilson Baniwa, who exhibited in Vexoa before co-curating Amazônia, extends this decolonial curatorial approach alongside Leandro Varison by integrating deeper time frames through archaeological perspectives into the dialogue between ethnographic collections and contemporary art. The result is a profound assessment of Amazonian peoples' reflection on this territory where millennia of human-forest co-creation have shaped worlds vital to all life on our planet. If you're anywhere near Bonn in March, go see it. You can also check out the catalogue and buy it online. If you can't make it, I hope you enjoyed this review.

Abel Rodriguez's works on the annual cycle of the Amazonian forest in Colombia. Photo by the author, September 2025.

Confluence is a space for discussing the entanglements among art, archaeology, anthropology, architecture, design, and environmental sciences.

Welcome to Confluences.

Every month, we'll gather here.